Autism: The New Normal

Greenwich magazine, June 2013

Twenty years ago, most people had never heard of autism. These days, chances are you know someone “on the spectrum.” The CDC now reports that one in 88 children are diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)—more than AIDS, diabetes and pediatric cancer combined. Cases have skyrocketed by 78 percent in the past six years, according to Autism Speaks, an organization founded by Southport’s Bob and Suzanne Wright. A prominent couple in our area and well beyond (Bob was vice chairman of GE and chairman and CEO of NBC Universal), the Wrights have a grandson with autism. They have used their influence to raise $200 million for research and to raise awareness globally, but no amount of clout can eliminate the toll autism takes on a family or instantly arrest its alarming growth.

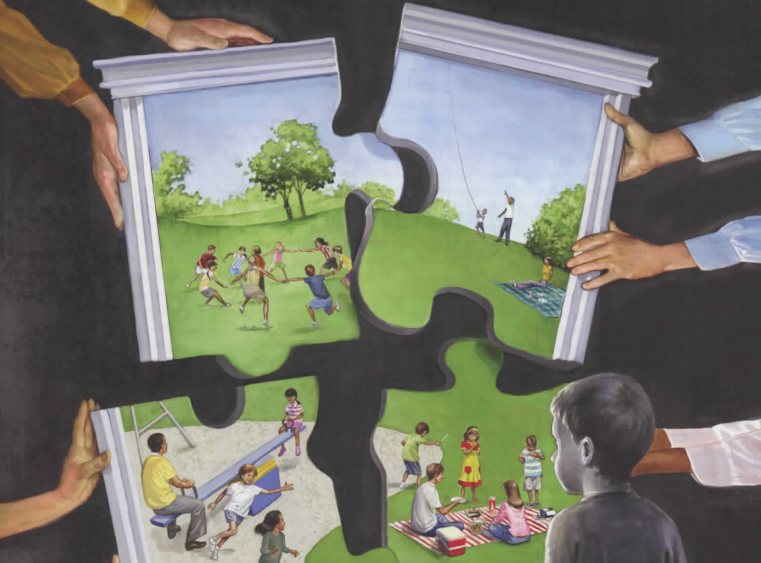

Allison Ziering Walmark, a Westport mom of a seven-year-old with autism, mourned when her son Ethan was diagnosed. “You go through the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance,” she explains. “Some people never really accept it.” One study puts the divorce rate for parents of children with autism at 80 percent (though some others note a lower rate). “It’s a day-to-day struggle, and you can have two parents who are perpetually in a funk.” Even though Ethan has a remarkable gift for music, Allison is constantly reminded of his challenges. “Kids look at him like he’s different,” she says. “When I look at a typical classroom, I see all the children playing together and I know my child is not like them.”

Defining the Spectrum

Dr. Jennifer Lee, medical director of St. Vincent’s Autism and Developmental Services at the Hall-Brooke campus in Westport, explains: “The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry defines autism as a neural developmental or biological condition with disturbances in three domains: impaired social interaction, problems with verbal and nonverbal communication, and unusual repetitive behaviors or severely limited interests or activities.” The only way to test for autism is to observe and assess a child’s behavior in these areas; there is no X-ray or blood test that offers a definitive diagnosis. Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Syndrome, Rett Syndrome, Childhood Disintegrative Disorder and Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) all fall on the “spectrum,” which is actually more of a net. This net catches a range of cases, from a nonverbal person with profound autism to a highly intelligent but socially awkward individual with Asperger’s. (It’s worth noting here that, despite some misconceptions generated by media coverage of the Newtown massacre, there is no known link between violent crimes and Asperger’s syndrome or any other ASD. “In fact,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reports, “studies of court records suggest that people with autism are less likely to engage in criminal behavior of any kind compared with the general population; and people with Asperger’s syndrome, specifically, are not convicted of crimes at higher rates than the general population.”)

A new version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) was set to be released at press time. It will require doctors to take severity of symptoms into account in determining whether someone has an ASD, and certain cases of “autism” may be reclassified as intellectual disabilities. Some parents are worried their children may lose eligibility for services they are currently receiving. This concern is only one of many when it comes to autism.

Do We Know the Cause?

Researchers have theories and parents have hunches, but as of yet, no one has a definitive answer. “Autism is not caused by one genetic defect,” says Dr. Lee. “There are multiple factors: a genetic component, environmental impact (which can either decrease or increase probability), and a neurological or structural piece.” Most scientists agree that both genes and something (or many things) in the environment play a role, but no one has determined exactly what is tipping the scales. Theories have included an overly sterile environment, the cutting of umbilical cords too abruptly and the hotly debated vaccine link.

In 1998, a study by Dr. Andrew Wakefield in England pinpointed the MMR vaccine. However, in 2010 his research was rejected and his license was taken away. But vaccine suspicions persist, which has led to an increase in parents who choose not to vaccinate their children. “There was a big measles outbreak in England recently,” Dr. Lee says. “Measles can be incredibly serious. I’m sure parents are coming from a place of love for their kids, but if you don’t vaccinate your children, realize the risk you are taking with other illnesses. Once vaccinations drop to a certain level, herd immunity doesn’t

function anymore, so there’s also a social responsibility.”

New Canaan resident Tom Murphy* questions the medical community’s stand on vaccines. “There are too many cases of kids with autism whose parents saw a major change within days after vaccine shots,” he comments. “Their kids were talking and then stopped, for example.” His eight-year-old son was labeled autistic six years ago, around the same time he was diagnosed with PANDAS, an autoimmune disorder associated with strep. Murphy says, “He couldn’t fight off colds or flus, so I don’t think he had the antibody levels to tolerate the vaccines he was given.” Dr. Denis A. Bouboulis in Darien, an expert on PANDAS, treated Murphy’s son with antibody injections. “His tics and seizures went away immediately but other symptoms lingered,” says Murphy, whose younger daughter was diagnosed with autism but is now off the spectrum after intense therapy starting at six months of age. “I truly believe that if she’d had a vaccine, it would have been horrible. We’ll gradually give them once we’re comfortable with her antibody levels.”Ulrika Drinkall, a Greenwich mother of three boys including one with autism, says, “My personal view is that autism can be triggered by certain things.” Her youngest, Gabriel, has a chromosome 2 deletion (his cells are missing part of the genetic material on that chromosome), which may be linked to autism. He also had a brain injury in utero. “I have two other boys who are not autistic and have the same genetic makeup—the same parents,” says Ulrika. “Maybe the brain injury was the trigger.”

Last March, a link between advanced paternal age and autism made the headlines. The study, involving 1.3 million children in Denmark, showed that men age thirty-five to thirty-nine have a 1.3 times higher risk of having an autistic child, and those over forty have 1.4 times the risk. “This isn’t a new idea. Ten years ago autism was seen as the province of upper middle class families with older parents,” says Dr. Lee. “Advanced maternal age is linked to many things. We now know the age of the father and mother are jointly associated with autism, but why? Is it chromosomal like Down syndrome? We don’t know yet.”

Another recent study in Denmark showed that flu during pregnancy doubled the odds of having a child with autism, and fever for more than a week tripled them, indicating the mother’s immune system plays a role. To reassure women, 99 percent of women who report flu or fever during pregnancy do not have children with an ASD.

The Diagnostic Maze

Parents with children diagnosed in the 1980s were told they were the unlucky one in 10,000. “Now it’s one in fifty-four boys and one in 252 girls,” says Autism Speaks founder Bob Wright. “In New Jersey, where I grew up, I have at least fifteen friends with kids on the spectrum, and that’s just friends I talk to,” comments Tom Murphy.

What is going on?

An environmental factor is likely, but Dr. Susan Dieterich, a psychologist who works closely with Dr. Lee at St. Vincent’s, notes, “It’s partly due to increased awareness and better tools for diagnosing. Also, when the DSM-4 came out, it captured more kids. A lot of kids who used to be categorized as mentally retarded are now diagnosed as autistic.” Dr. William Horn, psychologist for Greenwich public schools, adds, “Pediatricians now screen children for autism as part of their eighteen-month checkup, which historically they did not do.”

Dr. Dieterich suggests over-diagnosis is a possibility: “Borderline cases have always been hard; is it just a quirky kid or is it autism?”

No child on the spectrum is a carbon copy of another, so careful diagnosis is crucial. You notice your toddler is different. He’s fixated on spinning objects and shows no interest in peers—many of whom are acquiring words, while your little guy is not. But perhaps he also is affectionate and makes eye contact. Is it autism? A pediatrician will often refer parents to a specialist or the school may call Birth to Three, a state program that does home-based evaluations and early intervention for children with developmental concerns.

Murphy’s son was good with numbers and reading at two and a half, but “he had sensory issues—he didn’t want to walk on sand with bare feet and loud noises bothered him,” says Murphy. “He had some OCD behavior; he needed everything in order.” The Murphy’s pediatrician sent them to a neurologist. “He looked at him for twenty minutes and said, ‘Your son absolutely does not have autism,’” recounts Murphy. “How could he rule it out from a twenty-minute test?”

At St. Vincent’s, Dr. Dieterich’s evaluation involves hours of “cognitive, memory, academic and autism specific measures.” Dr. Lee conducts a clinical interview with the family and reviews medical history. “We decide on the diagnosis together,” says Lee. “Often you only have one piece, a psychologist or psychiatrist. We’ve got two disciplines working very closely together.”

Dr. Lee notes that autism can be confused with other disorders, such as hearing problems, ADHD, anxiety disorders and social phobias. The Murphy’s son eventually was also diagnosed with Lyme disease, which, like autism, can cause impulse control issues and OCD, clouding the diagnosis. Greenwich school psychologist Dr. Horn adds, “A child with Asperger’s can get misdiagnosed as having behavioral issues, when their behaviors are more coping mechanisms.”

“If you misdiagnose someone, they may not be getting the correct or optimal treatment,” says Dr. Lee. They also may not be getting coverage. Autism Speaks has been instrumental in getting laws passed in thirty-two states, including Connecticut, that require private health insurance policies to cover the diagnosis and treatment of ASDs.

Treatment Can Make All the Difference

Thirty years ago, doctors believed there wasn’t much they could do for kids with autism. “Some doctors would have suggested institutionalization,” explains Dr. Horn. Then, in 1987, Dr. Ivar Lovaas at UCLA, who had been experimenting with using applied behavioral analysis (ABA) to treat autism, published his findings. He reported that through a system of rewards and consequences, autistic children can learn. “What’s important is early identification and intensity of intervention,” says Dr. Horn. “Time is of the essence.” Unlike many other approaches, ABA is supported by decades of empirical research.

Dr. Susan Izeman, director of the Abilis Autism Program in Greenwich, says, “Children who receive intensive services before age two have really promising outcomes. That’s when their brains are changing the most.” Parents can make an impact as well. “The inclination is to do what the child wants, to avoid a tantrum,” explains Dr. Izeman. “Push against the rigidity now, because it’s easier to manage when they’re little than when they are twenty-one. It’s OK for your child to be upset. The more they learn to do, the more places they will go, the more flexible they become.”

Gabriel Drinkall is still undergoing an autism evaluation at Yale, but he is going to the SEED Center in Stamford nine hours per week on top of school. “I decided to put him in a center even though the diagnosis isn’t clear because there is so much therapy you can do for autism,” says Ulrika. “We’re trying all angles, including a holistic approach: changes in diet, supplements and vitamins, probiotics, attention to lead levels. We see

Dr. Pratt, a naturopath in Stamford. The first time we saw her, Gabriel was eighteen months old and couldn’t crawl yet. She did several hours of brain integration therapy (a technique based on the principles of applied physiology and acupressure) with him. We came home and he crawled across the floor.”

Gabriel does not take any medication. The only one specifically approved for autism is Risperdal, an adult anti-psychotic medication. It is used to treat irritability in autistic children. “The minority of autistic patients need medication,” says Dr. Lee. “Since each person has different symptoms, treatment needs to be tailored on an individual level.”

Kathy Roberts, founder of Giant Steps, a not-for-profit private school in Southport serving forty students with ASDs, stresses the medical aspect of treatment. When Norwalk Hospital called her to ask what to do with a nonverbal autistic man who was biting people, Kathy suggested they do a dental X-ray. As she suspected, he had a toothache. It had been a trying road to reach that level of insight. Five years ago, Kathy’s autistic daughter, then twenty-four, was diagnosed with a rare metabolic disorder that had been causing pain and vomiting for much of her life. “She had tantrums, but I was absolutely convinced there was something else going on that looked to me like pain. Ongoing medical care for kids on the spectrum is critical because they can have problems like migraines, reflux, constipation, but often don’t have the language to describe their ailments.”

Fortunately, there are many centers for autism treatment in our area (see p. 86, “Where to Turn”). “Anyone who says they have the answer, don’t trust them,” Kathy cautions. “You need people who will work with you to figure it out.” Dr. Horn suggests checking the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (bacb.com) to find qualified therapists and quackwatch.com for scientific evaluations of treatments.

The Right School

Public or private? It’s a question that is more complex when the issue is autism, not fancy sports facilities and AP courses.

Dr. Horn started working at Greenwich public schools in 1981 and helped develop the early childhood program. “The goal is to teach children in an environment that is closest to the natural environment,” he explains. “We try to integrate students with special needs to the greatest degree possible. That does not mean every child can function within the typical environment, but we start from that assumption and make modifications as needed.” Public schools typically employ teachers with advanced degrees in special education. “If extra support is needed,” says Dr. Horn, “we usually assign a professional assistant to the classroom rather than to the student. The problem with a one-to-one is the child may learn to respond only to that individual.” Kids who need it receive occupational therapy, speech/language and physical therapy.

“Public schools cannot refuse a child. Legislation says we have to try, and we have to try really hard,” says Dr. Horn. “If a significant lack of progress is documented, then we evaluate if the public school can provide what they need. By law, every child is entitled to a ‘free and appropriate public education.’” This means the government funds private education for students whose needs cannot be met at public school. It is important for parents to educate themselves on their rights.

Dr. Horn recommends reading the guidebook Negotiating the Special Education Maze.

“If a child’s needs will be met in public school, it’s the best thing to do,” says Kathy. “It’s easiest for the family. It doesn’t work for all kids, though. We’re pretty good at spotting who those kids might be.”

Giant Steps offers a spacious environment and everything from daily living skills to therapeutic horseback riding. “Buddies,” students from typical elementary schools, come and interact with the Giant Steps students in a reverse inclusion program, and a pre-vocational program readies older students for the adult world. “One of our graduates does data input at the Red Cross. Another installs doorknobs,” notes Kathy. “These kids are perfectionists; if you find the right skill for them, they can be very good employees.” One student with a gift for music—he sat down and played an Elton John song on the piano at age nine, having never played before—now entertains at kids’ parties. Another graduated from Babson College.

The public schools often refer students to Giant Steps and anyone can call to set up a free screening. “We encourage parents to come in, walk through the school and ask as many questions as they want. If the school feels right, they’ll know it,” says Kathy. “We maintain a short waiting list when we anticipate a student moving or graduating. It is our policy to counsel families and help find alternative placements, rather than maintain a long waiting list.” Tuition at Giant Steps is $120,000 per year (if the student is referred by a public school, the state foots the bill). “Residential programs are two to three times that,” adds Kathy.

Seana Littlewood and her family moved from England to Greenwich in 2011 with their autistic pre-teen, Josh. “We went to see Giant Steps and knew immediately that was the right fit for him,” she explains. Josh wore diapers until age six and “he had no form of communication at all then,” says Seana. “At eleven he turned a corner and started using a booklet with pictures to help form sentences. Then he began to use language without it.”

Paul Morris, one of quadruplets born in 1987 (the only one with autism), attended Weston High School. “He was at a private school, but he wanted to be with his siblings,” says his mother, Robin Hausman Morris. “He learned to navigate better socially going to school with typical kids.” Paul went on to attend the College Internship Program in Lee, Massachusetts, and now works part-time doing data entry. He has traveled by himself as far as Boston and set up and hosted an autism speaker series at Yale. All this from a guy who couldn’t form a complete sentence until age nine.

Autism in Adulthood

Half a million autistic teens in the U.S. are on the brink of adulthood. The dwindling of services and funding after age twenty-one will throw many of their families into crisis. “It’s exciting to see that adults with autism can continue to learn and grow, but it’s challenging figuring out how to pay for it,” says Dr. Izeman at Abilis, which offers programs from Birth to Three through adulthood.

Dr. Izeman designed the LIFE program, focusing on life skills, independence, friendship and employment for young adults. The skills they learn—walking down the street independently, grocery shopping, being

aware of their appearance before heading to work—may seem simple but they can be huge milestones for someone with autism.

Autism Speaks is working with Advancing Futures for Adults with Autism (AFAA) and has held a think tank on improving employment opportunities for people with autism. Autism Speaks also has developed tools to guide families as their children approach adulthood: a Transition Tool Kit, an Employment Tool Kit, and a Housing and Residential Supports Tool Kit.

“The percentage of autistic adults who can live independently is very low,” says Kathy. Paul Morris has been living on his own for three years, with the help of a service that checks in with him. However, his mom comments, “He cannot support himself independently.”

Greenwich’s Brita Darany von Regensburg, mother of a thirty-three-year-old daughter with profound autism and founder of Friends of Autistic People (FAP), has spent the past fifteen years advocating for autism awareness and funding. She warns, “The less we do now, the more money it will cost us later.”

In adulthood, Brita’s daughter Vanessa has been relegated to a group home where the staff is not trained to understand autism. “At age twenty-one, speech services and therapy programs that would help her continue to learn were taken away,” says Brita. “As a pretty girl, Vanessa is vulnerable. She needs to learn how to communicate.” After discovering disturbing evidence that their daughter had been sexually assaulted, Vanessa’s parents moved her to a different home, but her care is still far from ideal. “Often when I visit her, I can see that she is upset. She likes me to hug her tightly and sway back and forth. She has such courage to get up every morning, and every day she is ready to learn.”

FAP offers free workshops on everything from financial planning to sexual issues. In the future, Brita hopes to raise the $1.5 million needed to open a Farm Academy in Fairfield County, a living and learning center with farm animals, crafts, a music and art department, and open space for long walks—a utopia for adults with autism.

The autism road is a long one, but hope lies in early diagnosis, better treatment, greater awareness and increased funding. The Drinkalls follow this philosophy: “We realized we’re not going to cure Gabriel, but we’re going to make his life as good as possible.” While scientists search for a cure, the rest of us can work toward that same goal.